Bilateral Spastic Paralysis (Spastic Paraplegia) الشلل التشنجي ثنائي الجانب

Normal 0 false false false EN-US X-NONE AR-SA MicrosoftInternetExplorer4

Bilateral Spastic Paralysis ( Spastic Paraplegia )

INSTRUCTION

Carry out a neurological examination of this patient's lower limbs.

SALIENT FEATURES

History

· Ask about onset, duration and course of symptoms. · Back pain - is it localized'? · Ask about radicular pain.

· Numbness and paraesthesia, particularly below the level of the lesion.

· Weakness: gradual or sudden'?

· Sphincter control and bladder sensation.

· Functional status: wheel chair transfers, walking aids, orthotic shoes, has house been modified for the patient's disability'?

· Take a family history (hereditary spastic paraplegia).

· Take a history of birth anoxia (cerebral palsy).

· History of urinary infections, pressure sores and deep venous thromboses.

Examination

· Increased tone in both lower limbs.

· Hyper-reflexia.

· Ankle clonus

· Weakness in both lower limbs.

· Wasting.

Proceed as follows:

· Check the sensory level and examine the spine (spinal tenderness or deformity)

· Tell the examiner that you would like to do the following:

-check sacral sensation

-examine the hands to rule out involvement of upper limbs

-check for cerebellar signs (multiple sclerosis, Friedreich's ataxia).

· Try to localize the level of lesion using the following:

-spasticity of the lower limb alone: lesion of thoracic cord (T2-L1)

-irregular spasticity of lower limbs with flaccid weakness of scattered muscles

of lower limbs: lesion of lumbosacral enlargement (L2-S2)

- radicular pain: useful early in the disease, with time becomes diffuse and ceases

to have localizing value

-superficial sensation: not good for localizing as the level of sensory loss ,nay

vary greatly in difterent individuals and in different types of lesions.

DIAGNOSIS

This patient has bilateral spastic paraparesis (lesion) at L I spinal level due to trauma (aetiology); it is complicated by bladder

involvement (functional status).

QUESTIONS

What are the causes of spastic paraparesis?

Youth:

· Trauma.

· Multiple sclerosis.

· Friedreich's ataxia.

· HIV.

Adults':

· Multiple sclerosis.

· HIV (Neurology 1989; 39: 892).

· Trauma (motor vehicle or diving accident).

· Spinal cord tumour (meningioma, neuroma).

· Motor neuron disease.

· Syringomyelia.

· Subacute combined degeneration of the cord (associated peripheral neuropathy).

· Tabes dorsalis.

· Transverse myelitis.

· Familial spastic paraplegia.

Elderly:

· Osteoarthritis of the cervical spine.

· Vitamin deficiency.

· Metastatic carcinoma.

· Anterior spinal artery thrombosis.

· Atherosclerosis of spinal cord vasculature.

ADVANCED-LEVEL QUESTIONS

What intracranial cause for spastic paraparesis do you know of?

Parasagittal falx meningioma.

What do you know about paraplegia-in-flexion?

Paraplegia-in-flexion is seen in partial transection of the cord where the limbs are involuntarily flexed at the hips and knees because

the extensors are more paralysed than the flexors. In complete transection of the spinal cord, the extrapyramidal tracts are also

affected and hence no voluntary movement of the limb is possible, resulting in paraplegia-in-extension.

What do you know about transverse myelitic syndrome?

· Causes include: trauma, compression by bony changes or tumour, vascular disease.

· All the tracts of the spinal cord are involved.

· The chief clinical manifestation is spastic or flaccid paralysis.

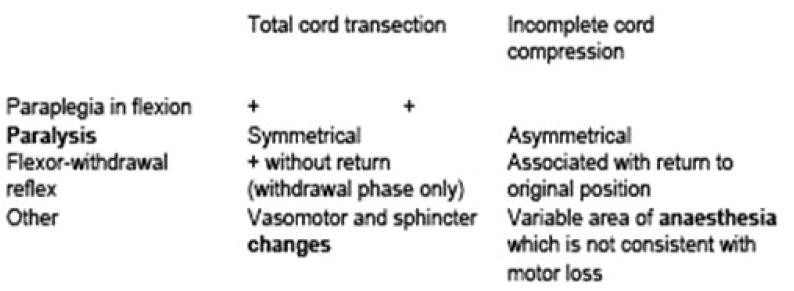

· The lesion can be incomplete cord compression or total cord transection:

What investigations would you perform ?

· Complete blood count (CBC) for anaemia; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) for infection.

· Serology: syphilis, vitamin B12, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and serum acid phosphatase, and serum protein

electrophoresis.

· Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the spine.

· Computed tomography (CT) of the head to exclude parasagittal meningiomas.

· CT myelography, or plain CT.

· Check cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) for oligoclonal bands.

· Serum vitamin B12 levels.

Where is the lesion in patients with spastic weakness of one leg?

The lesion may be localized to the spinal cord or the brain. Progression to involve the arm does not help to differentiate between the

spinal cord or the brain. Similarly, spread to the opposite leg does not necessarily indicate that the lesion is the spinal cord. Full

investigation would include radiography of the spine and CT, but if the latter is normal then myelography may be required.

What do you know about hereditary spastic paraplegia?

This is an autosomal dominant condition, first described by Seeligmuller and Strumpell, in which spasticity is more striking than

muscular weakness. The age of onset is variable and the condition has a relatively benign course. When the onset is in childhood,

there may be shortening of the Achilles tendon, often requiring surgical lengthening. There is usually no sensory disturbance.

What do you know about tropical spastic paraplegia?

This is seen in Japan, the Caribbean and parts of western Africaand South America where women, more often than men, in their

third and fourth decades have spastic paraparesis with neurogenic bladder. Viral infection with human T-lympbotrophic virus I has

been implicated as a cause of this disorder.

How do you localize the lesion to the 2nd and 3rd lumbar root level?

· Muscular weakness: hip flexors and quadriceps.

· Deep tendon reflexes affected: knee jerk.

· Radicular pain/paraesthesia: anterior aspect of thigh, groin and testicle.

· Superficial sensory deficit: anterior thigh.

How do you localize the lesion to the 4th lumbar root level?

· Muscular weakness: quadriceps, tibialis anterior and posterior.

· Deep tendon reflexes affected: knee jerk.

,, Radicular pain/paraesthesia: anteromedial aspect of the leg.

· Superficial sensory deficit: anteromedial aspect of the leg.

How do you localize the lesion to the 5th lumbar root level?

· Muscular weakness: hamstrings, peroneus longus, extensors of all the toes.

· Deep tendon reflexes affected: none.

· Radicular pain/paraesthesia: buttock, posterolateral thigh, anterolateral leg, dorsum of [bot.

· Superficial sensory deficit: dorsum of the foot and anterolateral aspect of the leg.

How do you localize the lesion to the 1st sacral root level?

· Muscular weakness: plantar flexors, extensor digitorum brevis, peroneus longus, hamstrings.

· Deep tendon reflexes affected: ankle jerk.

· Radicular pain/paraesthesia: buttock, back of thigh, calf and lateral border of the loot.

· Superficial sensory deficit: lateral border of the foot.

How do you localize the lesion to the lower sacral root level?

· Muscular weakness: none

· Deep tendon reflexes affected: none (but anal reflex impaired).

· Radicular pain/paraesthesia: buttock and back of thigh.

· Superficial sensory deficit: saddle and perianal areas.

What is the characteristic type of diplegia in cerebral palsy?

Diplegia associated with prematurity is a striking clinical entity striking for the symmetry of neurological signs, for their distribution, for

the relatively good intelli-gence of the patients, and for the comparative absence of seizures, the disability often being purely motor

without sensory deficits.

What surgical treatment is available for the management of spastic diplegia in cerebral palsy?

Dorsal rhizotomy may be beneficial in selected patients.

What are the clinical features of spinal cord compression from

epidural metastasis? The initial symptom is progressive axial pain, referred or radicular, which may last for days to months.

Recumbency frequently aggravates the pain, unlike the pain of degenerative joint disease where it is relieved. Weakness, sensory

loss and incon-tinence typically develop after the pain. Once a neurological deficit appears, it can evolve rapidly to paraplegia over a

period of hours to days. In suspected cases MR! of the spine must be done by the next day. About 50% of cases in adults arise from

breast, lung or prostate cancer. Compression usually occurs in the setting of dis-seminated disease. It is at the thoracic level in 70%

of cases, lumbar in 20% and cervical in 10%, and occurs at multiple, non-contiguous levels in less than half of the cases. The

tumour usually occupies the anterior or anterolateral spinal canal. CSF findings are non-specific in metastatic epidural compression.

The cell count is usually normal, bu! protein levels may be raised because the flow of CSF is impeded. Lumbar puncture has been

known to worsen the neurological deficit, presumably due to impaction of the cord.